THE BACKSTORY

The Mongol Rally is a driving adventure (not a race) from London, England to Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. The organization that plans the rally coordinates launch parties, car import into Mongolia and finish line parties…the rest is up to the individual teams. In 2013, 240 cars signed up to take on the challenge. Among those teams was Attila the Pun, a team from the US originally formed by Ian Nichols and Jon Hay, two friends from undergraduate study at Harvard University. In late March, Matt Nelson, a friend of Jon’s from Booth business school, joined the team. The group of three was all set to embark on the journey together, when in early June Jon got his dream job, which forced him to drop out. Having never actually met previously, Matt and Ian came face-to-face for the first time in a hotel bar in London, England. After less than 24 hours together (which was plenty of time for us to hit it off), we picked up our car, a Nissan Almera with a 1.5-liter engine, which we affectionately nicknamed Jon Hay, but identified as a female to distinguish from our mutual friend back home. We immediately set out for Scotland for a week of sightseeing and also to learn the ways of a right-hand drive car (new for Ian) with a manual transmission (new for Matt). While there, we toured Edinburgh, went Scotch tasting and got locked out in Inverness, circled the Isle of Skye and met up with a couple of Matt’s college buddies in St. Andrew’s. The team of two returned to England (after several hours parked on M-6 due to a road closure) for the official Mongol Rally launch party at Bodiam Castle, about 60 miles south of London.

THE RALLY BEGINS

On June 14, 2013 Attila the Pun embarked on their wild adventure. Committed to not using GPS and having not yet acquired maps, the team was at a bit of a disadvantage from the get go. We followed other teams as best we could towards Dover (where we would catch the ferry across the English Channel to France), but at one point we caught a red light and lost the cars in front of us. All of a sudden we were leading a caravan of rally cars without any idea where we were going. We were essentially following cars behind us — when they put on their blinker, we turned. Fortunately we made it to Dover where we stopped at a gas station and purchased an atlas of Europe. We rode the ferry across the channel and set out for Frankfurt, Germany. We made it through France and half way across Belgium before stopping for dinner in Brussels. We had so much fun there that we stayed for the night. In true rally fashion, plans were already changing.

CZECH OUT PARTY

It wasn’t exactly smooth sailing getting out of Brussels, but we eventually were on our way headed towards the second launch party at Klenova Castle, 80 miles southwest of Prague, Czech Republic. We crossed Germany at very high rates of speed (on the autobahn) and very low rates of speed (due to a toxic spill) and found the castle (despite more navigational issues) around dusk. After an enjoyable second launch party with nearly all the 240 teams, we were one of the first teams off the next morning. We didn’t get more than a few miles before we momentarily lost control of the car and ended up in a fender bender which left us with a punctured radiator and some body damage to the car. Sorting things out with the police (who didn’t speak any English) and coordinating a tow took nearly the whole day, during which time nearly every other rally team drove by. More than 20 stopped to offer help, but there wasn’t much that could be done. It then took another 24 hours to get the car repaired (thanks Petr!), so after 3.5 days we were already 1.5 days behind the other teams.

PLAYING CATCH UP

A lot of the fun of the rally is caravaning with other rally teams, so we wanted to make up the time lost in the Czech Republic. We skipped one of our two planned nights in Vienna, Austria and then after two nights in Budapest, Hungary (where the hose to our laundry machine popped off the wall and flooded our bathroom…and Matt got hilariously lost walking the streets), we again chose to forgo one of two nights in Bucharest, Romania in order to fully catch up. By the time we reached the Romania/Moldova border (despite delays due to a tipped over semi truck), there were several other rally cars in line with us. We’d caught up!

REGISTRATION

The enjoyment of having caught up with other teams lasted all of the way until the Moldova side of the border where we were turned away and sent back to Romania (which included us getting a tire stuck in an open manhole while driving towards oncoming traffic on our way back). Apparently the copy of the vehicle registration we’d received when we’d picked up our car back in the UK was fine for traveling within the European Union where border crossings were either non-existent or officials could look up our registration in their systems. However, once we tried to leave the EU, as we were doing by trying to enter Maldova, only the original registration document was acceptable. This original document is mailed by the DVLA (UK version of DMV) to the address to which the vehicle is registered 2-3 weeks after the official purchase. We were right in that window, so we contacted the DVLA to see if they could send the registration directly to us in Romania. No luck, the document was already in the mail. This meant that the registration was headed to the residence of an extended family friend back in the UK who had been kind enough to let us use her address for our car registration. Of course she was having construction done so she was not home, but rather in Connecticut. This meant we needed to relay messages to her in CT, which she would then relay to a construction worker on site. The whole Romania to US to UK communication process usually took a full 24 hours given all the time changes. The construction worker went through all the mail at the house in London (which was considerable given the family’s absence due to the construction), but the registration document hadn’t yet arrived. The waiting game began. And then the royal baby was born and mail delivery ceased for a couple days so we waited some more. When the mail finally resumed, our document arrived and the construction worker overnighted it via DHL. In all, we spent three nights in the border town of Galati and two more nights back in Bucharest in addition to the one we’d spent there on our initial trip through, for a total of six nights in Romania. But we were finally back on our way (thanks Sonia and Brian!).

PLAYING CATCH UP…AGAIN

We were once again behind our fellow ralliers, this time by almost a week, and we were adamant about catching up. Despite some navigation issues we made it back to the border and successfully into Moldova…which was literally on fire. There was some sort of massive fire in a field that extended for miles but fortunately did not impede our progress. Moldova itself is only about 30 miles wide where we crossed, so it seemed like the whole of the country was on fire. Regardless, we made it across the border and into Ukraine (without the need for a “green card” — a piece of paper that entry officials insisted we’d need in order to exit). We then hauled across southern Ukraine (and a very strange 5-mile stretch back in Moldova), to Odessa where our European atlas ended and we got very lost trying to find our hotel. It certainly didn’t help that the Ukrainians (and all subsequent countries) used the Cyrillic alphabet, which introduced several entirely unfamiliar characters in addition to many familiar letters taking on entirely different sounds (for instance, their “P” makes our “R” sound). We ended up purchasing a folding map that spanned from Romania to the Russia/Mongolia border. We’d set out from Bucharest, Romania at around 2 PM and finally arrived at our hotel in Odessa, Ukraine around 7 AM. After a little over 24 hours in Odessa, we were back on the road and quite literally chased out of the city by a pack of wild dogs. We drove throughout the morning only to discover when we stopped for gas/lunch that our rear bumper had somehow fallen off somewhere along the way. We’d traveled too far to turn back and look for it, but miraculously during lunch, a trucker entered the restaurant, asked if that was our car parked outside and indicated that he had our bumper in his truck. A little duct tape later, Jon Hay was once again whole.

We put the rest of Ukraine behind us that afternoon (including some sort of fight where one guy was hitting another with a large stick outside a depot store) and entered Russia the following morning. We blew through most of Russia in one day, including the very poor roads in and around Volgograd, and made it to the border city of Astrakhan.

THE SCARIEST ENCOUNTER OF THE TRIP

Figuring that the roads would get a little dicier when we entered the ‘stans (they’d already been pretty bad since entering Ukraine), we had coordinated to meet with a mechanic in Astrakhan to help us with some preventative alterations to Jon Hay. The mechanic told us that lodging in the city was outrageously expensive and that he’d hook us up with some much more affordable accommodations. We met him at a McDonalds around 9 PM and he led us down some ridiculously dark, dingy back roads before turning into what seemed like an abandoned warehouse complex. As we wound through the unlit complex, through giant potholes and puddles, we were certain that there was going to be a gang of Russian mafia waiting around each corner to kill us or, at best, take everything we had and leave us for dead. We stopped at a two story building and the mechanic — who we knew only as Sam — jumped out and started yelling back and forth with a woman on the second floor. After this interaction he came over to our car and informed us we could stay there. We were too scared to decline the offer. The room had green track lighting, no windows, no sink and no TV. It looked more like a place you’d rent by the hour than for an evening. We only half slept and were sure to keep all our valuables on our persons, still worried that a gang of mafia thugs would come barging in.

As it turns out, no one came to rob or kill us and Sam showed up as promised the next morning and couldn’t have been nicer about helping us out. He took us all over Astrakhan getting us new, more rugged, all-weather tires and a couple new rims for two of our old street tires, which he strapped to our roof for us to keep as spares. He reattached out bumper and added a couple metal guards underneath our car to protect our fuel line and tank. He even took us to an outdoors store and grocery (where we stocked up on supplies for the rest of the trip), then led us out of the city and got us back on our way.

KAZAKHSTAN AND UZBEKISTAN

After leaving Sam, we made our way for the Russia/Kazakhstan border, which led us across a bridge that was probably half a mile long and literally just floated atop the water. We entered Kazakhstan in the dark of night with little fanfare and quickly found a place to set up camp. Despite having two stoves and multiple fuel tanks, none of them were actually compatible, so meals were uncooked and consisted of salami, cheese and nuts.

We awoke the next day to policemen quickly flipping their sirens as they passed along the road. We’re still not entirely sure what this meant, but it proved to be a recurring theme as this happened three of our four mornings in Kazakhstan (I guess we hid too well the other morning). We drove into Atyrau where we stopped to get car insurance and a tourist stamp (required of all visitors who stay in the country longer than 5 days). This was easier said than done, but after several stops taking up the better part of the day, we were ultimately successful on both accounts.

The next few days, we covered most of western Kazakhstan with many interesting moments along the way. In one instance, wind currents created by passing trucks kept causing our spare tires to pull against their strap, which eventually created so much extra tension that the strap broke. Luckily we noticed before the tires slid off the roof and we re-attached the tires with the remaining — albeit slightly shorter — length of strap. In another instance, after driving most of the day without passing a single gas station, we were finally within sight of a station in the outskirts of Aralsk when our car sputtered to a stop. Fortunately, we had previously overestimated the amount of gas we needed by about one liter when filling up near the Russia/Kazakhstan border and had decided to save the extra liter in a gas can. At the time, we’d laughed about saving such a trivial amount (relative to our 70-liter tank), but that amount proved to be exactly what we needed to make the last kilometer to the gas station in Aralsk. Other stories include: getting pulled over for driving without our headlights, using a roofless three-walled outhouse in the driving rain and the unfortunate experience of hitting over a dozen birds in just a few hours as whole flocks continually darted in front of our car.

Through it all, we made it to the Kazakhstan/Uzbekistan border…at least so we thought. The border, however, was only open to foot traffic. We ended up driving for another seven hours up and down the border looking for a place to cross before finally being led to the right location by a local man who had run after our car and flagged us down after hearing us be given the wrong directions at a gas station. This border crossing was much more exciting as we were asked for “souvenirs” at just about every stop of the way and were witness to a fist fight between truckers jockeying for position in the line to enter Kazakhstan. Once in Uzbekistan, we were further harassed for souvenirs by traffic officials who flagged us over for not coming to a complete stop at their checkpoint and for driving with open-toed shoes.

We finally made it to Samarkand around 4 AM and followed a taxi to the Ideal Hotel where we slept on couches because they no longer had rooms available. We spent a good couple of days with Amir and Shahboz, our friendly hotel hosts and toured the ancient city (including a tour of a museum located a block away from the museum we thought we were visiting). When it came time to move on, we asked about gas stations and it turned out that there was only one legitimate gas station in the whole city and we ended up having to wait an hour to fill up.

On our way to the Tajikistan border, we caught Genghis Style, a Mongol Rally team from near Manchester, England consisting of Andrew, Greg, Mark and Amy. They were basically the first ralliers we’d seen on the road since getting denied at the Moldova border. Later in the same run for the border, we caught another Mongol Rally team called Langstrasse Extended, made up of Robert and Andrea from Zurich, Switzerland. At one point, the three teams stopped to chat, but had to quickly abort the discussions when we were basically mobbed by locals who were interested to see what the deal was with three sticker-laden cars rolling into town. We caravaned the rest of the way to the border where we found a fourth Mongol Rally team, Team Fishbowl, our two favorite folks from the launch parties (before we got derailed in the Czech Rep and Romania). The team consisted of Katie aka “KP” and Mitch from just outside Byron Bay, Australia. The border was closed for the evening, but Fishbowl had bigger problems because their Uzbek visas had expired. We enjoyed a fun night as a group of four teams, but the next day we pressed on without our Australian friends.

TAJIKISTAN AND KYRGYZSTAN

After some difficulties with some local kids who insisted on washing our car for money, we set out to cross the border, but we encountered serious delays when a customs agent on the Tajikistan side was nearly three hours late for work. We eventually made it to the city of Dushanbe where we were supposed to pick up a care package (from Ian’s brother David) with stove fuel, a tarp and a compass among other useful items. We went to what was supposed to be the DHL office, but we were informed that they had moved locations nearly 10 years prior. A very nice man, however, led us across town to the new facility where we successfully retrieved our parcel of goodies (thanks David!). Back in central Dushanbe, we split up to run a couple errands, but Matt got lost trying to reconvene and ended up walking around for nearly an hour. The three teams, however, successfully made it out of town and commenced the journey to the Pamir Highway, a famously treacherous but extremely beautiful stretch of road along the Tajikistan/Afghanistan border.

We hit the Pamir Highway and continued on to the Wakhan Corridor, skirting the Afghanistan border for 420 miles of indescribably challenging roads that rewarded us with the most beautifully panoramic views of the entire trip. Along the way, we made our first cooked meal, were awoken by a herd of over 100 goats being driven through our camp, gave gas to a stranded night-traveler in a Lexus, stalled Jon Hay while coming face-to-face with a couple donkeys while rounding a steep blind turn, lost our power steering, boiled our coolant (which we subsequently replaced with creek water) due to a broken fan blocking air flow to our engine, Matt got altitude sickness, the Brits lost their shocks and the Swiss rolled their car (and were robbed by people who were “helping” them get the car going again).

Back on the main roads of Tajikistan, we ascended to the highest altitude of the trip (15,317 feet), made a brief detour into China and then pushed for the Kyrgyzstan border before our Tajik visas expired. We were still at 13,814 feet when we hit the Tajik side of the border.

Now it’s not uncommon to have large stretches of “no-man’s land” between countries where neither country takes responsibility for the roads (which end up in disrepair), but the area between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan was absolutely ridiculous. We drove for nearly 45 minutes, crossing three rivers — two where we drove straight across and another where we actually had to jog and drive within the river for a stretch. We also followed an elevated two-lane road that had become a one-lane road because the river below had eaten away the embankment to the point that one lane had fallen off into the water. By the time we approached the Kyrgyzstan side of the border, we had descended over 2,500 feet and were in the midst of a driving, freezing rain.

It was unclear whether it was the rain or the overall lack of traffic at such a remote location, but the Kyrgyzstan border crossing was absolutely deserted. We drove all the way to the end of the crossing without seeing a sole, so we got out and knocked on the door of the nearest building. A man answered, looked at us, looked at our car and asked if we spoke Russian. When we shook our heads, he asked if we had narcotics. We again shook our heads and he waved us on and closed the door. No passport check, no stamp, no car search…we even had to open the gate for ourselves as we drove out.

From there, over the next four hours, we descended another 10,000 feet to the city of Osh. Since our caravan mates both had car issues to which they needed to attend, we once again set out on our own. Our giant map was usually sufficient to navigate from one town to the next, but it offered virtually no help navigating within cities. We had a Central Asia guidebook that had small city maps, but reconciling those with the large map was often challenging. So when we entered the capital city of Bishkek, we decided to just follow the main road until we figured out where we were on the smaller map. We had just identified our location when we were pulled over by a police officer. For all intents and purposes we had been following all the rules of the road, so we had a lot of difficulty figuring out what we’d done wrong. The cops kept trying to explain and we kept saying that we didn’t understand and pointing to our hotel on the map as an indication of where we were trying to go. As it turns out, despite sticking to the main road, we’d somehow unknowingly entered a pedestrian-only thoroughfare. You’d think something like that would be better marked. The cops then escorted us out of the pedestrian-only area and to our hotel where we were supposed to pay a hefty fine. When we arrived, the cops hopped out and lit up cigarettes, which gave us a great idea. Matt had purchased a carton of 10 packs of cigarettes for $30 at a duty free shop when flying from SF to London, so we gave each officer a pack in exchange for letting us off. $6 of cigarettes (from two non-smokers) in exchange for a cop escort and not having to pay a hefty fine…not a bad deal.

The next day we got our power steering fixed and once again hit the road, crossing the length of Kyrgyzstan (meanwhile getting pulled over for our one and only speeding ticket of the trip). It was 7 PM in eastern Kyrgyzstan and we were deciding whether or not to make a run for the Kazakhstan border when we commenced the most ridiculous 36 hours ever.

THE MOST RIDICULOUS 36 HOURS EVER

[If you read nothing else, you should read the detailed description of this earlier in our blog]

We were about 50 miles from the Kazakhstan border and it didn’t get dark until after 8 PM, so we decided to go for it. We were heading at a fairly steady pace when a car decided to pass us…only it didn’t get all the way in front of us before trying to merge back into our lane, nearly clipping our car. They then decided to go much slower than we had been going so we passed them back. This only lasted for a minute or so before the car decided to pass us again. This time they only got half way past us before deciding to merge back into our lane, forcing us to slam the brakes and swerve off the road. But instead of carrying on ahead, the other car immediately did a U-turn and headed off in the other direction. Entirely baffled by what had just occurred, we continued on. We were still discussing what had just transpired when, less than two minutes later, a kid who was riding his bicycle alongside the road in the same direction as us decided he wanted to head back the other direction and without looking just flipped around into in the road facing us. We had less than 15 meters to slam on the brakes and skid to a stop. Our run to the border was already proving more difficult than we had anticipated.

The roads leading to and from border crossings are typically not well kept and this was no exception. But as we continued on, the roads got so bad that we were essentially driving on a one-car service road covered in rocks and giant rain-filled potholes. On top of that, it had been nearly an hour and a half, was completely dark and we were passing military helicopters and army tents…things we really didn’t think we were supposed to be driving past. We decided to double back, but after an hour in the other direction we still didn’t see any turnoffs towards the border. We decided to once again head back the way we had originally come and this time we saw a sign for a left turn. The turn was virtually invisible in the dark as it led down the side of the elevated road. Interestingly, looking back on our travels of the evening, our jaunt down what had appeared to be a service road was actually us following along the Kyrgyzstan/Kazakhstan border headed towards China.

Once back on track, we found the border in no time. The only problem was that it had closed at 6 PM. This whole run for the border had been entirely for naught. We set up camp and prepared to be the first across in the morning.

The border crossing started with some excitement as we couldn’t find our car registration (the same document that had caused us so many problems back in Romania). Fortunately we eventually found it wedged in the top of our overly stuffed glove box. But the problems didn’t stop there. Since we didn’t have entry stamps in our passports, the officials claimed that we must have broken into the country. On top of that, none of them were high enough ranking to accept a bribe, so we had to wait six hours for a man to come “approve” our exit from the country (we later read that this “no stamp/pay fine” thing happens pretty frequently in Kyrgyzstan). The Kazakh side of the border was a much smoother process, but we only made it one kilometer into the country before our “Check Oil” light came on and our engine started to knock.

We pulled over and discovered that at some point over the course of trying to find the border the previous evening, we must have punctured our oil pan on a rock. The oil presumably drained out overnight, leaving us with just enough oil left in the engine to make it across the border, but not much further. To address the issue, we ripped the cover off our Tajikistan guidebook and tried duct taping that over the puncture, but the oil still drained out. In the US, while car troubles are 1) infrequent on the well-paved roads and 2) often easily address with something like AAA, the opposite is true throughout Central Asia. Cars break down all the time and people must rely on the assistance of passersby in order to get back on the road. As such, though, the people of Central Asia are generally much more sympathetic to the plight of the stalled. Fortunately for us, a passing family took pity and towed us 15 miles to the nearest little town, which was about 10 blocks by 10 blocks in size.

The tiny town had no official mechanic, so our friend Nurlan must have towed us to eight different houses before finally finding a place that would take us in. However, in the brief time it took for us to drive the car through the gate, the “mechanic” decided (based on the noise from the engine) that not only could he not fix our car, but no one in the town could either. We needed to be towed to the nearest city, Almaty, which was about 150 miles away. Since Nurlan was the only person there who spoke any English, he relayed to us that a tow truck was on its way to take us to a mechanic in Almaty. It would be $250 and we shouldn’t pay until we arrived. It was getting late, so we thanked him and sent him and his family on their way, but that left us without anyone else who spoke the same language.

The language barrier immediately became an issue when the “tow truck” arrived and it turned out to actually be just a normal semi truck. We were unsure as to what was transpiring, but they tied our car to the back of the truck and we started on our way. We traveled only a few blocks before the truck stopped and without even attempting to communicate with us, the driver untied the car and started driving away. What?!?!? Before we had enough time to fully panic, the driver looped around below us and backed up to the embankment. He produced two rickety wooden planks (one the width of a tire and the other about half as wide) and we used these to bridge the gap between the embankment and the back of the truck. We pushed our car across the planks and into the truck (with the help of a drunk who then harassed us for some sort of payment), pulled the emergency brake and joined the driver and his son in the cabin of the truck. We drove a couple more blocks to the nearest gas station where the driver demanded payment. Despite being told to not pay until Almaty, it was clear that he needed the money for gas, so we paid him.

After filling up, we drove just a few blocks before stopping for a third time. This time, again without any attempt to communicate, the driver and his son both hopped out of the truck and disappeared behind a fence. We sat alone in the truck wondering what the heck was going on. He already had our money and had just taken off. After nearly an hour, the driver and his son returned to the truck (maybe they stopped for dinner?) and we finally set out for Almaty.

The truck had many of its own issues (difficulty getting into first gear, a door that randomly came unhinged) and it took a lot longer than expected, but we eventually made our way into the city around 2:30 AM. There were a few unanswered questions on our minds. First, how were we going to get the car back to street level? Second, will the mechanic actually be in his shop at 3 AM? And finally, if he’s not there, what are we supposed to do with ourselves and the car until he arrives?

We got the answer to the first question when the truck pulled into an abandoned rail yard somewhere just north of the city. It turns out (not so surprisingly so in retrospect) that train platforms are the exact same height as the flatbeds of semi trucks. However, as he backed up to the platform, the truck was on a bit of an incline, so we essentially needed to push the car uphill to get it out of the truck. On top of that, the car had shifted around during the drive and had wedged into a corner (knocking out a headlight in the process) so that the driver’s door and the front of the car were both up against the walls of the truck. This meant that Ian could not help with pushing while steering the car and that Matt needed to prop his feet up against the vertical front wall of the truck with his hands on the front of the car (so he was horizontal to the ground about three feet in the air) in order to push. The truck driver tied a rope to the rear bumper and pulled while Matt pushed and Ian steered and the three of us eventually got the car out onto the platform.

We rolled the car from the platform down a dirt path to street level and waited for the truck driver to reattach the tow rope and take us to the mechanic. That, however, clearly wasn’t part of his agenda as he took the remainder of his money and drove off. Thus, we found ourselves stranded in an abandoned rail yard somewhere north of Almaty at 3 AM with a broken car, no mechanic, no cell phone reception and no money (we’d given the last of it to the driver for the tow). We were exhausted from getting the car out of the back of the truck, but we managed to push it off the lot and a kilometer to what seemed like a normal intersection. There wasn’t much left we could do, so we reclined our chairs and grabbed four hours of sleep in the car. We would get up and figure things out at 7 AM, exactly 36 hours after we decided to make a run for the Kyrgyzstan/Kazakhstan border.

ALMATY

We awoke on Friday morning to the hustle and bustle of a busy street with people walking everywhere. A man was even sweeping the sidewalk around our car. Things were coming together though. There was a grocery store across the street with an ATM inside and Ian all of a sudden had cell phone reception and was able to call for a tow to a mechanic.

The shop thought they could have the oil pan repaired within 24 hours, but after further inspection they realized they also needed to replace parts within the engine and the parts supplier was closed for the weekend. It ended up taking 6 days to get the car back in working shape…during which time an awesome thing happened: our Russian visas expired.

As it turns out, the visa office at the Russian consulate in Almaty is only open on Tuesdays and Fridays from 9:30 AM to 12:30 PM — a grand total of six hours a week. Unfamiliar with how to proceed, we showed up on the first Tuesday and asked the man whether we needed to extend our old visas or get completely new ones. The man informed us that we needed new visas and that the application must be filled out online and printed. He wrote down the URL on a piece of paper and sent us on our merry way. We filled out our applications, had passport photos taken, found a place to print everything and even ascertained that we needed letters of invitation, which we coordinated to have emailed to us by a company in Russia. We showed up at the consulate on Friday with all our new application information, but the man informed us that while we were indeed making progress, we still needed the original letters of invitation (not just print outs), our car registration and proof of insurance. We immediately contacted the company in Russia and they sent the letters via DHL. The expected arrival, however, was Tuesday between 9 AM and 12 PM. If they were any later we’d miss another window at the consulate. Fortunately, the letters arrived on time and the man at the consulate was able to process everything. We were good to go, right? Wrong. The consulate doesn’t do same-day processing, so we needed to come back on Friday to actually pick up our visas. It took us two full weeks from the time we determined that we needed new visas to when we finally had them in our hands.

It wasn’t all bad though. At the mechanic shop, the only English speaking person was a woman in her 20′s named Alta who had given us her number to call for updates. Instead we called her and invited her to dinner with us and the Swiss folks from the Langstrasse Extended rally team (who managed to catch up after dealing with their own car issues back in Kyrgyzstan). Apparently Alta thought we were okay people because we ended up hanging out with her pretty regularly over the course of our two-week stay. Each time we met up, Alta brought a new friend to meet us. It got to the point that we knew so many people and had been in Almaty so long that we were considering throwing a going away party when we were finally able to get back on the road.

We tried meeting other people as well, but they didn’t all work out as well. Ainur Akkuzhina wanted to meet up to chat with Ian about hedge funds, but the conversation spiraled way out of control. It got to the point that she started claiming that our agreeing to meet her was all some sort of elaborate rouse and that Ian hadn’t ever worked for a hedge fund. It was the most uncomfortable interaction of our entire lives.

MONGOLIA

Back on the road and now two weeks behind schedule, we powered across Kazakhstan and through Russia. Along the way, we dealt with the metal guard (protecting our fuel line) coming loose and dragging on the ground (which we fixed with a bungee chord) and an incident at a Russian gas station where the attendant failed to tell us that our credit cards didn’t work until after we’d filled our tank (Matt had to leave Ian as collateral while he followed a hand written map to an ATM). Through it all, however, we made it to the Mongolian border on the morning of September 2. It took the better part of the day (including some issues getting an immigration stamp on the Russian side and an extended lunch break on the Mongolia side), but by 5 PM we were officially in Mongolia. We’d reached our destination country!

With over 1,000 miles of the most challenging roads still ahead of us and with no legitimate map extending beyond the Russia/Mongolia border, we were by no means to the finish line just yet. There were only two main routes across Mongolia — a northern and a southern route (we took the southern) — with dirt roads that split in ten different directions only to converge again with the main road a short distance later . Within our first 24 hours in the country alone, we helped a broken down car, Matt had a crazy fever, our protective guard came loose several times, we had to push out of some mud where we somehow lost our guard entirely, we got a rock wedged in our tire assembly, we crossed four rivers and we drove the wrong way down a one-way street.

Things didn’t get much easier from there as we came close to death twice in the next couple days. The first time, we were cruising at freeway speed along a nice elevated paved road when, without warning, the pavement dropped away and pretty abruptly descended back down to a ground-level dirt road. We launched off the end of the pavement and caught some air, but fortunately made a fairly smooth landing. The second time, we were driving on a not-nearly-as-nice, dirt-laden elevated paved road when we were confronted with a sizable trench in the asphalt. We swerved to avoid it, but this caused our tires to skid uncontrollably on the thin layer of dirt in the road. We cut back the other direction and the wheels caught right before the car was about to careen into a ditch alongside the road. This, however, sent the tires skidding the other direction. We slid back and forth across the entire road multiple times in each direction. Ultimately, the car did a full 180-degree tailspin at which point we were finally able to slam on the brakes and come to a safe stop.

We came away from two near-death experiences unscathed, but Jon Hay wasn’t faring as well. Her radio hadn’t worked since Almaty and her air conditioning gave out on the roads of Mongolia. Then, for good measure, the bindings on her exhaust pipe gave out and we had to tie the pipe back in place with pieces of clothesline. Of course the heat of the exhaust melted the line, so we had to repeat this patchwork process several times before some friendly passersby gave us some metal wiring to use. We would later lose the casing around our exhaust pipe, but the pipe itself stayed in place.

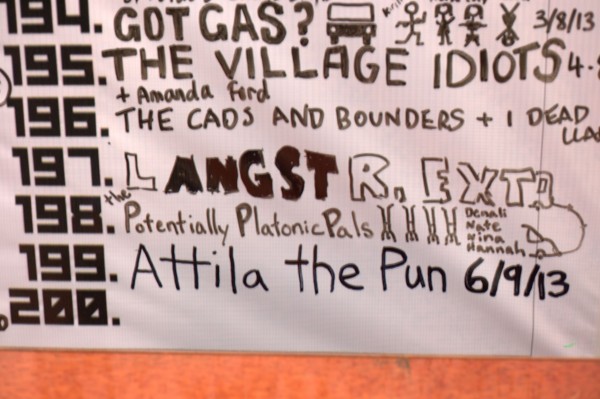

It was a long challenging journey with lots of ups and downs, but after eight weeks, 12,045 miles, 16 countries and 11 non-EU border crossings, we reached the finish line in Ulaanbaatar early in the morning of September 6, 2013. Despite being told to anticipate taking 5-7 days to brave the perils of the Mongolian roads, we had done it in less than four. On that day, two tuxedo- and headband-clad men with significant beards were the 199th team to write our team name on the huge board at the Chinggis Khaan Hotel finish line.